The University of Oregon's Covid-19 testing unit, the Monitoring and Assessment Program, recently concluded operations after collecting 285,626 samples and detecting 9,827 positive cases. The program not only proved to be successful in monitoring and tracking cases within the state of Oregon, it also made evident that universities hold the talent, technology and determination to serve communities in times of crisis.

This article first appeared on Around the O on August 31st 2023.

The University of Oregon’s COVID-19 testing lab, the Monitoring and Assessment Program (MAP), operated from 2020-2023. During that time, MAP staff collected 285,626 samples and detected 9,827 positive cases. Beyond facilitating safe living conditions for UO students through two major COVID-19 surges, MAP provided testing to Lane County and to K-12 schools in southern and central Oregon in 168 schools in 26 school districts, enabling a safer return to in-person instruction. The lab also worked with Latinx communities throughout the state and partnered with HIV Alliance to provide testing to underserved communities, thanks to funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

But MAP’s impact is far greater than these statistics. The program imparted a valuable lesson: Universities have the latent talent, technology, determination, partnerships, and logistical capability to serve the community and state during a crisis.

Should We Buy It or Can We Make It?

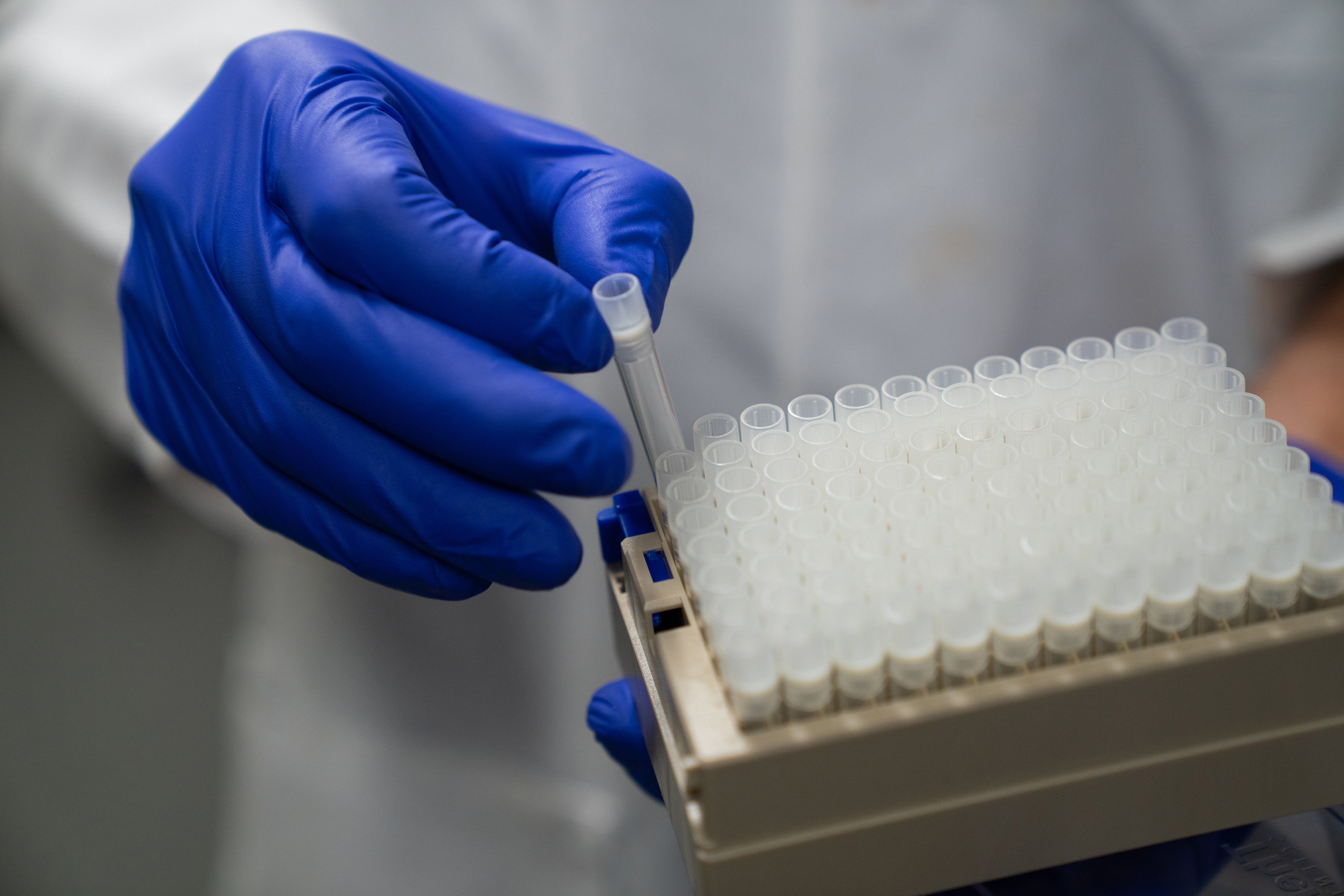

In the early days of the initial shutdown, the decision to purchase a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) machine was the choice on which all future work hinged. Greg Shabram, UO’s chief procurement officer and self-proclaimed current events buff, had been watching COVID-19’s rapid march across Asia months before it was identified in the U.S. The existential threat all universities faced when the shutdown came was the catalyst for the UO to act.

“There’s always the question of ‘should I buy it, or can I make it?’” Shabram said. With the conviction that the UO wouldn’t be able to rely on a third party for testing, he worked with senior leadership to facilitate the purchase of the critical tech."

“We had the expertise, the people, and the equipment to make it work. The result of that initial decision and the many that followed is that we provided highly accurate and short turnaround-time testing to our community throughout the pandemic. It contributed to reducing the spread of COVID-19 in Lane County.” — Greg Shabram

Through supply chain issues large and small (from a dearth of lab coats and pipettes to stockpiling nearly every available green folder in the US), UO’s Purchasing and Contracting Services navigated the hundreds of daily decisions necessary to build MAP into the testing powerhouse it became.

Along with Greg Shabram, professors Leslie Leve and Bill Cresko were tapped to head the MAP leadership team. Both managed large teams prior to the pandemic, and those teams from the Prevention Science Institute and the Data Science Initiative pivoted into MAP roles.

Into the Fire

Though “flying by the seat of our pants” is perhaps a flippant description of the process of building a federally certified testing lab from the ground up, it’s also not an inaccurate one. The initial days were chaotic as people were pulled from all corners of the university to stand up MAP, but the depth of UO’s team quickly proved itself an asset: UO was the first university in the state to offer mass testing.

“This this all came together at a university without a medical center or school of public health,” said Gretchen Drew, then director of operations for the Data Science Initiative — who suddenly found her master’s degree in arts administration deeply useful in entirely unanticipated ways. “But we realized that we were the type of people who apparently run into the fire, instead of away from it.”

From the Volkswagen Eurovan “office” parked in her driveway with an ethernet cable snaking into the house, Drew found herself a maestro of logistics alongside others, including Anna Shamble (at that time with the Office of the Provost), and later, Marta Slattery, who served as the final director of operations for MAP.

“We cleared barriers and we worked together to apply expertise and learn rapidly,” Drew said. “As the lab was being built, we were also thinking about resilience."

That protocol included providing testing for students, faculty, and staff at the UO first. Later, those tools and systems were leveraged to provide testing in multiple counties, communities, and school districts in Oregon.

“It is the most important thing I’ve ever done professionally,” she said, though she acknowledged the personal toll that came with the around-the-clock meetings and unceasing problem solving. “There was burnout associated with it. When many people were at home baking bread, we were not. I still don’t know how to bake sourdough.”

Thinking Outside the Box

The team the UO assembled, which included UO-based geneticists and human subjects researchers, project managers, truck drivers, and student workers — as well as essential public health partners and experts from Lane County Public Health and Oregon Health Authority — proved that pulling together capable people and having no preconceived notions about how to run a testing lab was an asset. Teams couldn’t get bogged down in “this is how we’ve always done it” narratives because building up MAP was entirely new. Those involved quickly understood that occasional false positives or failed test runs were part of a rapidly changing disease pathology and operating at very high throughput levels. These problems could be solved, piece by piece. Ariana White, who served as the technical supervisor for the lab, smoothed out many of the bumps in the road.

“We looked at this as a public health problem, not a health care problem,” said Brian Fox, associate vice president for budget, financial analysis and data analytics and MAP’s executive director during the scale-up phase.

Scaling up, at the end of the day, was a matter of logistics. Units like Campus Planning and Facilities Management and Information Services, so often in the background of day-to-day university operations, became leaders as everyone focused on achieving the same goal: Stop the spread of COVID-19 so life in and out of the university can continue normally.

“Like research, it was a learning and iterating process,” Fox said. “Building and running MAP was about understanding operations management and an innovation cycle. You push a bit, learn lessons, and where you have failures, you pull back and figure out what’s driving it, then push a bit more.”

Putting Skills, New and Old, to Use

The UO flexed its creative might in more ways than one: The university was part of a group of West Coast institutions that pioneered a DNA sequencing-based testing method that was ultimately overtaken by a streamlined saliva-based qPCR test developed at Yale University that didn’t require the time-consuming step of viral RNA purification. However, building on momentum, UO iterated on Yale’s process to achieve higher testing throughput by inactivating saliva samples with a simple heat treatment process instead of complex enzymatic reactions — a modification that was written into Yale’s FDA-approved testing protocol and used by higher education institutions across the country.

This capability to try and try again served the UO well when the Oregon Health Authority called on the state’s health care providers around the state to ramp up testing for K-12 schools.

“We had one week to prove we could do it,” said Doug Turnbull director of the MAP testing lab and the Genomics and Cell Characterization Core Facility (GC3F), which performed viral DNA sequencing for MAP. “Partially why we could do it so quickly is we weren’t trying to fit it into an existing paradigm. Population-scale testing is very different from a hospital testing lab that runs single samples at a time. We built MAP from ground-up to be run at a population-level. The people in GC3F who worked on this had never been called upon to do anything like it, but we had the skills that were needed.”

The university also called upon those it serves: students. Despite the many challenges posed by the pandemic, a positive aspect is the real-world training opportunities it provided to many.

“During the pandemic, we leveraged student support a lot,” said Leslie Leve, the Lorry Lokey Chair in Education and scientist at the Prevention Science Institute. “It created an opportunity for students’ hands-on skill development. They helped with testing and processing samples. In the classroom, the pandemic provided an opportunity to talk about the essential nature of collaboration and cross-disciplinary science because there are multiple types of expertise needed to solve crises related to human health. Collaboration is important from the earliest stages of your career onward.”

For some faculty and staff, the responding to the pandemic also fostered a blossoming of new research directions.

“It was a transformation for the institution, and for many of us individually. We now know we can rise to a challenge like this in the future,” said Bill Cresko, Lorry Lokey Chair and professor of biology. “It opens avenues of research that we hadn’t attempted because of perceived huge hurdles that the pandemic forced us to leap over. The NIH grant for Latinx communities — I wouldn’t have done that before. We realized we could pull the resources together. We had to stretch ourselves in so many ways.”

And while COVID-19 forced many people to rethink their life situations, be it their jobs or where they lived, it also gave those who do research for a living the opportunity to reflect.

“I’m an evolutionary geneticist. I never thought I’d be doing work in the area of human subjects, but it ended up being the work I think I’ll take the most satisfaction in for the rest of my life. There were probably hundreds of lives saved because of the testing we put together,” he said.

Moving On

When the federal COVID-19 public health emergency declaration expired May 11, it came with a pervasive sense of anticlimax. Though those involved were grateful that overall, COVID-19 was far less deadly than it could have been, it also signaled the end of one of the most memorable periods in recent history.

“In 2020, when I would tell people I was working on COVID testing and developing a new test, the response was amazement,” Turnbull said. “Now I’m almost hesitant to mention what I did because people don’t want to think about what a pain it was back then. I feel melancholy at times about that hangover effect. We did all this work, and no one wants to think about it anymore.”

Cresko echoed this sentiment, comparing it to periods after some wars or horrendous natural disasters.

“If we subconsciously suppress our memories of that period, it’s to our detriment. We will experience these grand challenges again,” Cresko said. “Attention needs to be paid to the networks among higher education institutions, at state agencies, and at non-profit and community-based organizations so they can snap back when needed. I’m afraid by entering this period of amnesia, we’re letting the cords fray. Maintaining the tapestry doesn’t happen by chance. We need to care for these relationships so in the next crisis we can respond appropriately.”

Marta Slattery, final director of operations for MAP, said that the waning months of the lab made apparent that the need for testing availability was nearing its conclusion.

“The first year and a half of the pandemic was undeniably a sprint,” Slattery said. “We faced the daunting task of building systems from scratch, and during the Omicron variant’s peak, we had to respond to overwhelming demand: We were testing around 1,000 people daily. With treatments and vaccinations becoming more accessible, the need for our services naturally declined. However, as emergency responders, we understood the importance of remaining prepared for any potential resurgence, and many people were using the service until the last day. We streamlined and improved many of our processes in the last year of service and should the need arise again, we will be ready.”

MAP’s legacy — its role in slowing the spread of the virus, in giving schools the assurances they need to bring students back, in facilitating learning and research opportunities — is ultimately that it proved to the university, Eugene, and the state that the UO is a critical asset in preparing for and reacting to public crises.

— By Kelley Christensen, Office of the Vice President for Research and Innovation

Editor’s note: Hundreds of people contributed to MAP during the years it was in operation, and though they are not all named here, their efforts and resilience are not overlooked. The UO is profoundly grateful to everyone who participated for their good work.

Showing 1 reaction